But U.F.C. has become a global sports empire — and now commands an eye-popping price tag.

The league, which promotes mixed martial arts, is expected to announce as soon as Monday that it has sold itself to a group led by the talent giant WME-IMG for about $4 billion, according to people with direct knowledge of the matter. Backing the deal are the private equity heavyweights Silver Lake, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, and the investment firm of the billionaire Michael S. Dell.

The deal highlights the power and reach of the 23-year-old U.F.C., whose fights are now shown in more than 156 countries and take place in all 50 states, and which claims millennials as some 45 percent of its audience.

For its new owners, the league represents a prime source of content, particularly in the digital arena. Beyond its headline fights, which the company asserts are the best-selling events on pay-per-view TV, U.F.C. over all generates roughly 2,000 hours’ worth of material each year, much of it available on its Fight Pass streaming service.

For its new owners, the league represents a prime source of content, particularly in the digital arena. Beyond its headline fights, which the company asserts are the best-selling events on pay-per-view TV, U.F.C. over all generates roughly 2,000 hours’ worth of material each year, much of it available on its Fight Pass streaming service.

The transaction comes just as U.F.C. concluded its latest series of fights, perhaps the biggest in the organization’s history. (The event, U.F.C. 200, drew more than 18,000 fans to Las Vegas but was marred by some controversy, including the absence of stars like Ronda Rousey, Conor McGregor and Jon Jones, the last of whom was removed after testing positive for an undisclosed substance.

It will be a windfall for U.F.C.’s primary owners, the longtime casino entrepreneurs Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta, though they will stay on as minority investors.

The brothers bought U.F.C. in 2000 for just $2 million at a low point for the league, after the promoter spent years and millions of dollars battling to win approval from state athletic commissions.

Before the arrival of the Fertittas, U.F.C. had begun climbing in popularity, thanks to early stars like Royce Gracie and Ken Shamrock and a reputation for being just shy of civilized. But opposition loomed from Senator John McCain of Arizona, who derided the sport as “human cockfighting,” and former Governor George E. Pataki of New York, who banned the sport from the state.

The early years under the brothers — who run the business through a company called Zuffa, the Italian word for “fight” — were still tough, with million-dollar losses weighing over the enterprise.

But the Fertittas took the brand to a new level, with more advertising, more effective social media marketing and better distribution through partnerships like the one with Fox. Licensing money for video games, clothes and more began to roll in. U.F.C.’s revenue was about $600 million last year.

Respectability came along with rules meant to curb the excesses of early fights and getting approval from each state’s athletic commission. The last came this year, when New York lifted its ban on the sport.

And cross-promotional television programming like “The Ultimate Fighter” reality show elevated U.F.C.’s presence in pop culture, turning athletes like Chuck Liddell and Randy Couture into mainstream stars. Combatants began appearing on ESPN and in the pages of Sports Illustrated.

Successive generations of fighters, particularly Ms. Rousey, became even bigger celebrities.

U.F.C. has demonstrated enormous digital reach as well, particularly after the introduction of U.F.C. Fight Pass streaming service in late 2013.

Under the Fertittas, U.F.C. also swallowed up many of its competitors while pushing aggressively abroad, establishing beachheads in Europe, Asia and Australia. As part of that international campaign, Zuffa sold a minority stake in the promoter to an arm of the Abu Dhabi government six years ago.

Not all has been rosy for U.F.C., however. The league has faced accusations that it underpays many of its athletes. And it remains dogged by concerns about the brutality of some of its fights.

Along the way, the Fertittas, burly fighting enthusiasts who are bound to settle business disputes with a jujitsu match, have already earned themselves a fortune and amassed high-priced art collections.

Rumors about a sale of U.F.C. in a multibillion-dollar deal have percolated since the spring. In May, the company flatly denied being up for sale.

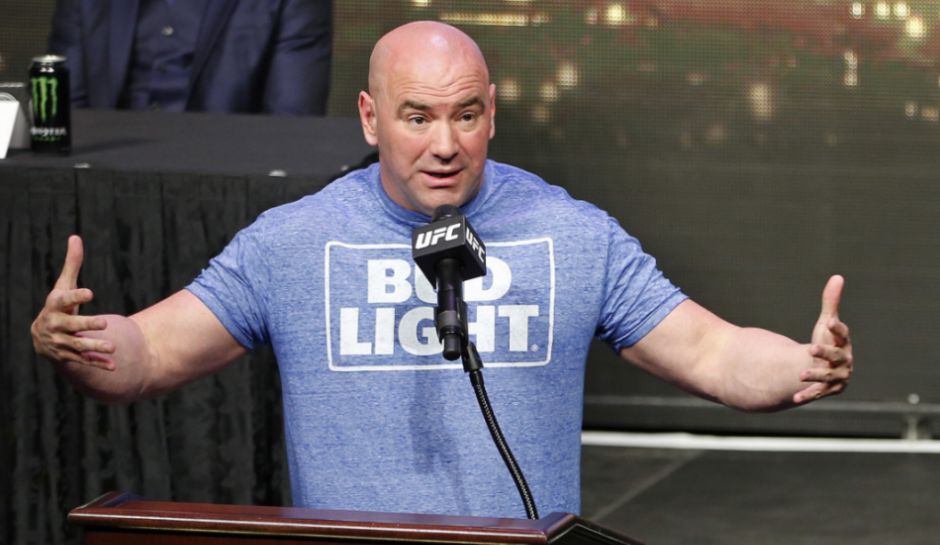

Its president, Dana White, said, “We’re not for sale,” though he conceded, “But let me tell you what. If somebody shows up with $4 billion, we can talk.”

As recently as last week, Lorenzo Fertitta and Mr. White denied that they had sold the business. “We own the U.F.C. We did not sell the U.F.C.,” Mr. White told The Los Angeles Times on Tuesday. (That’s true: The two sides signed the deal agreement over the weekend.)

Such is the popularity of the company that it drew interest from a number of suitors, including big Chinese media players that reportedly included the Dalian Wanda Group, which owns the AMC theater chain, and China Media Capital, which owns stakes in pro sports teams like the Manchester City soccer club.

But it was WME-IMG, which already represents stars like Ms. Rousey in media rights and has represented U.F.C. itself, that emerged victorious. For the Hollywood colossus, which is led by Ari Emanuel and Patrick Whitesell, acquiring U.F.C. is the latest step in creating a huge stable meant to command digital media.

The agency has gained financial firepower for such deals, taking investments this year from the Japanese telecommunications giant SoftBank and the mutual fund titan Fidelity.

WME-IMG has already taken steps into the sports world, buying the Professional Bull Riders league last year. Still, U.F.C. is a much bigger step in the agency’s goal to become a platform for content, to which it can apply a host of levers — from marketing to talent management to television and digital distribution.

Though WME-IMG represents Ms. Rousey and other combatants in their endorsements and movie deals, the agency will not get involved in the actual pay negotiations with athletes, according to the people with direct knowledge of the matter.

Backing the agency are Silver Lake, which led the merger of WME and IMG nearly three years ago and which has long pushed portfolio companies to become bigger through acquisitions, and K.K.R., which has often worked with Silver Lake on major investments like the takeovers of GoDaddy and the chip maker Avago.

Both firms will own minority stakes in U.F.C.

Mr. Dell has been allied with Silver Lake since the investment firm helped him take his computer empire private in 2013, and then aided him in buying the data storage company EMC last year in what was the biggest-ever takeover in technology. Mr. Dell’s firm, MSD Capital, will own preferred shares in the sports league, which will essentially pay out interest.